A supply of electric current in the house for lighting, cooking, and for the operation of the labor-saving household appliances is no longer looked on as a luxury.

—Preface to the Second Edition of Wiring Houses for Electric Light (1916)

Electricity in the house is a necessity.

The history of electrification focuses on watershed events like the opening of Pearl Street Station, or the refinements that brought the Edison incandescent light bulb into our homes. We learn about electrification by studying the power of the dynamo and the benefit it brought to us of light. We learn about electrification by the drama that was the “War of the Currents,” between the Nikola Tesla’s alternating current and Edison’s direct current. We think about power as generators and consumption. By and large, the histories we write overlook the carrier, the conduit that connects origin and destination—the copper wire conductor.

A wire is a conductor. That’s how electricians refer to the energized wires that connect your electric service to subordinate panels and then to the outlets and fixtures in your home. These strands of wire are conductors.

A conductor is a material that promotes a charged “flow”—an electric current. This is where the term “carrier current” comes from. In the business of “flow management,” electricity is another flow to be metered and managed. In this case, current is also an electrical flow that can carry a lower voltage rogue current, like radio frequency or direct current, into the house of a mobbing victim.

The “conductor” is the copper wire my electrician fishes through lathe-and-plaster walls to connect to an outlet. “Conductors” may have been what one possible social engineer wrote me about when she said the mobbers “can make the walls sing.” “Overhead conductors” are the high-voltage lines that transport power from generator to consumer. Conductors bring electrical supply to meet demand, much like the Ethernet cables or fiber lines that supply bandwidth to our homes. In mobbing, intrusion into household circuits may take the shape of jamming, glitching attacks, or denial of service. No matter the severity, these are man-in-the-middle attacks, exploits affecting our utilities and services, middle-manning civil rights, liberties—our very lives—every day.

Ω

The term conductor is not reserved for electrical systems. Any material that allows the flow of electric current is a conductor. According to Wikipedia, “[c]onduction materials include metals, electrolytes, superconductors, semiconductors, plasmas and some nonmetallic conductors such as graphite and conductive polymers” (“Electrical conductor, in Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Electrical_conductor.)

Metal is a common electrical conductor. For example, old galvanized pipe, that is, zinc-coated steel piping, is subject to galvanic corrosion. Balkan Sewer and Water Main describes the primary causes of galvanic corrosion:

There are three main causes of galvanic corrosion; direct current being transferred onto a water service line from the secondary electrical ground. Dissimilar metals are connected to each other, such as galvanized pipe and copper tubing. Lastly stray electric current running underground from damaged or defective underground utilities.

Galvanic corrosion, sometimes referred to as “lasagna,” was obvious in the galvanized incoming water line at the Albany house. My plumber updated the water line to copper. Also at the Albany house, when my Oakland electrician pointed out that a second ground rod is recommended these days, we added it.

This is where it becomes easier to understand how mobbing infects a home in a systemic manner, over any conductor that can be accessed, over the electric service and wires, and over the network of piping that channels flows like water and gas into and out of the homes of mobbing victims.

After the water line was updated to copper at the Albany house, the interior air-polluting effect from a Tesla being charged at the south property line was significantly diminished, though the electrical interference and radio frequency that the charging process produce appear to provide a substantial platform for other mobbing exploits. The family of a contractor purchased that house soon after my mother moved out my childhood home and not long after I began to tend the house at my mother’s request. As the contractor family began working on the garage (recently marked with a new address), they installed a charging appliance—probably a Tesla PowerWall based on Airtool collection. One of the owners of that house also appears to work for a locally based company promoting online investment in single-family rental homes.

Ω

Thomas Edison’s engineering of the 100 kilowatt dynamo established the capacity for power supply. The six direct current generators housed at Edison’s Pearl Street Station could light a square mile of New York City. Each of the 27-ton “Jumbo” generators was capable of powering 1200 lights (“Pearl Street Station,” in Engineering and Technology History Wiki, https://ethw.org/Pearl_Street_Station).

A dynamo employs a rotary electrical switch called a commutator to rectify and convert alternating current to direct current (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dynamo and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Commutator_(electric). In the traditional design, “electrical contacts called “brushes” made of a soft conductive material like carbon press against the commutator” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Commutator_(electric)). This design is compared to that of a vacuum cleaner motor, another device known for its “noisy” electrical design. This might be why medical device manufacturer Boston Scientific considers vacuum cleaners in their advisory on the use of pacemakers in environments where EMI is present (https://www.bostonscientific.com/en-US/patients-caregivers/device-support/pacemaker/emi.html). I do not know whether “smart” vacuum cleaners like the unsecured Tineco within WiFi range of the Seattle house as of late have brushes. According to Wikipedia, the brushless DC motors that are these days preferred use semiconductors.

Edison’s first goal in the project of electrification was to illuminate business and industry. Edison would demonstrate the efficiency of his own incandescent bulb whose design incorporated a thin carbon filament (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Electrification). The innovation of the incandescent light bulb would allow for the abandonment of highly flammable gas light systems.But there were numerous obstacles to illumination.

Tools that detected the flow and quantity of current emerged by the early 1800s but the capability to meter flows across time did not exist. Without metering, it would not be possible to accurately bill and create revenue. The science of utility and flow management would evolve with metering technology and lead to the bells and whistles of the “smart meter.” Another crucial and continuing issue was the problem of how to insulate electrified wires extended over a distribution system. LaLuce D. Mitchell, an architect in historic preservation, discusses the importance of electrical insulators in the evolution of electrical distribution systems:

When electricity came into use, it was seen as heralding a solution to all the problems of gas lighting, as it neither flickered, smelled, nor smoked. In exchange, however, electricity did bring the very real risk of fire, and due to unreliable distribution of power and poor wire insulation in its early years, fires were common, if not occasionally expected. A constant push was made to develop better insulation and distribution practices that would allow electricity to be a consistently safe method of providing power for the needs of daily life.

(“Early Electrical Wiring Systems in American Buildings, 1890-1930,” by LaLuce D. Mitchell, Association for Preservation Technology International (APT), Vol. 42, No. 4 (2011), pp. 39-45.)

Edison’s electrical distribution network in New York called for the installation of an elaborate system of wires—conductors—running through tubes called conduits. The expense added to the controversy of a project that required digging up city streets. In the end, the project was completed only after the intervention of the New York City mayor. The installation of the wiring system emphasized the importance of distribution in electrification. The New York Times, an early beneficiary of the project, reported the introduction of incandescent light to be “soft, mellow, grateful to the eye.”

Ω

The problem of power delivery from Pearl Street Station to business was solved with conduit. Shielded cable was considered too expensive for residential application. It was the knob-and-tube wiring system that brought light to the family home.

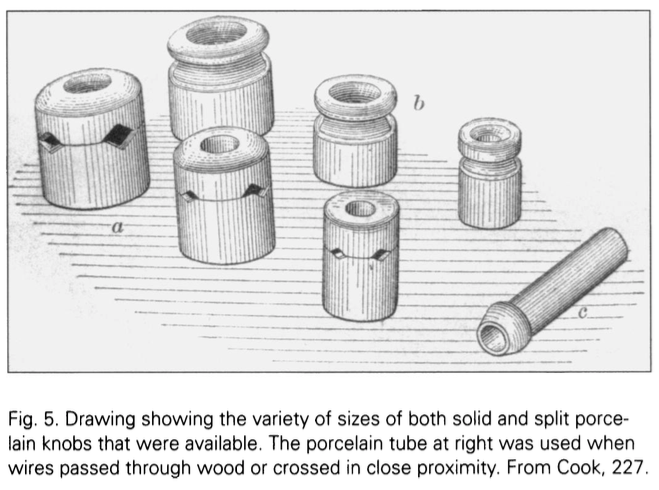

Edison devised the method of insulating runs of electrified wiring that became known as knob-and-tube. Inventor and engineer John D. Harden, Jr. explains in a Edison TechCenter presentation: “Initially [Edison would] just take copper bare wire and drill it through wood for the two conductors, and after a while it would trip out and blow fuses. So then he had to figure out a way how to insulate the wire.”

The solution was found in ceramics. Edison convinced master potter William Cermak to bring his family to the United States and create specialized ceramic pieces for the safe conduction of high voltage. The replacement of less capable glass insulators with ceramics fastened the lines of distribution between dynamo and dwelling (“Knob and Tube – early electrical insulation,” by Edison TechCenter with John D. Harden, Jr., inventor and retired General Electric engineer, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x8ekfxijhuA).

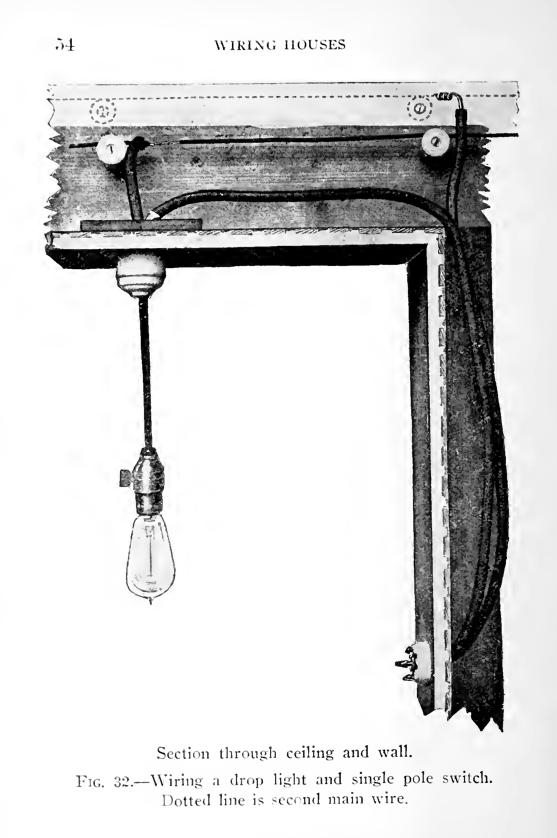

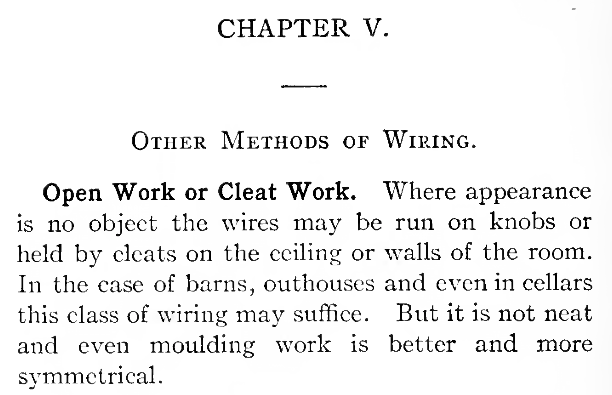

On December 31, 1879, Thomas Edison demonstrated interior illumination by a delivery system including the components of knob-and-tube wiring. The site was a boarding house for Edison workers tended by his relative Sarah Jordan. Perhaps for reasons of expediency, the wiring was installed as an exposed system. This is called “open work”; the author of Wiring Houses also refers to it as “cleat work”.

(For purposes of this entry, I use longer quotes than I typically would and show screenshots from the scanned original to better convey the care with which knob-and-tube wiring systems were installed.)

Electrical wiring systems that were installed in the 1880s and 1890s were commonly exposed. Perhaps this was because electrification remained experimental and was not part of a recognized process for home building. Mitchell states that the exposure was used as a status symbol and to ensure ease of access in the event of malfunction (p. 41).

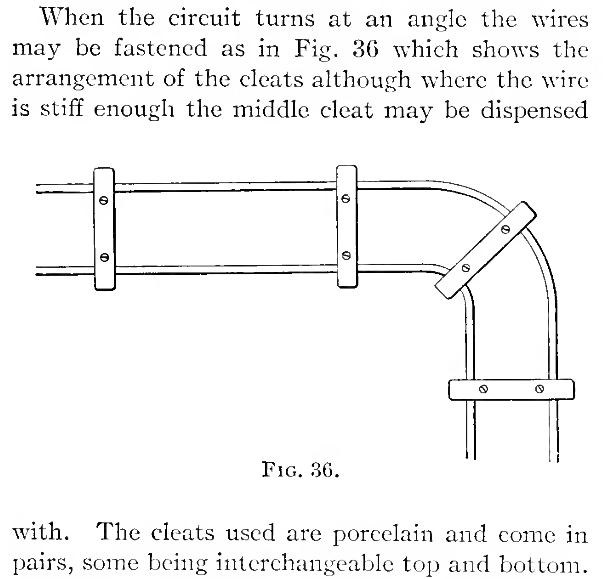

Open work also provided better dissipation of heat. This allowed the electrified wire to be run closer to the surface and secured one inch away using “cleats” instead of being held inches away by “knobs.”

The wiring system allowed for the demonstration of his incandescent bulb (“Thomas Edison Lights the Lamp,” https://archive.nytimes.com/learning.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/10/21/oct-21-1879-thomas-edison-lights-the-lamp/). A steam engine powered the three direct current dynamos that were required to light the bulbs (“Sarah Jordan Boarding House,” https://gfv1929.blogspot.com/2008/07/sarah-jordan-boarding-house.html).

Forty years had passed since the emergence of the first incandescent lamp (https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/edison-demonstrates-incandescent-light).

Ω

The open work wiring system was not widely used in houses though it remained in commercial use for inexpensive industrial applications into the 20th century. The knob-and-tube system of wiring remained a cost-effect strategy for residential installation.

The knob-and-tube wiring systems that travel the walls of our homes were carefully specified, customized, and intended for installation by skilled “wiremen.” The safety of the wiring system is wholly dependent on the quality of the installation and the standard to which it is maintained.

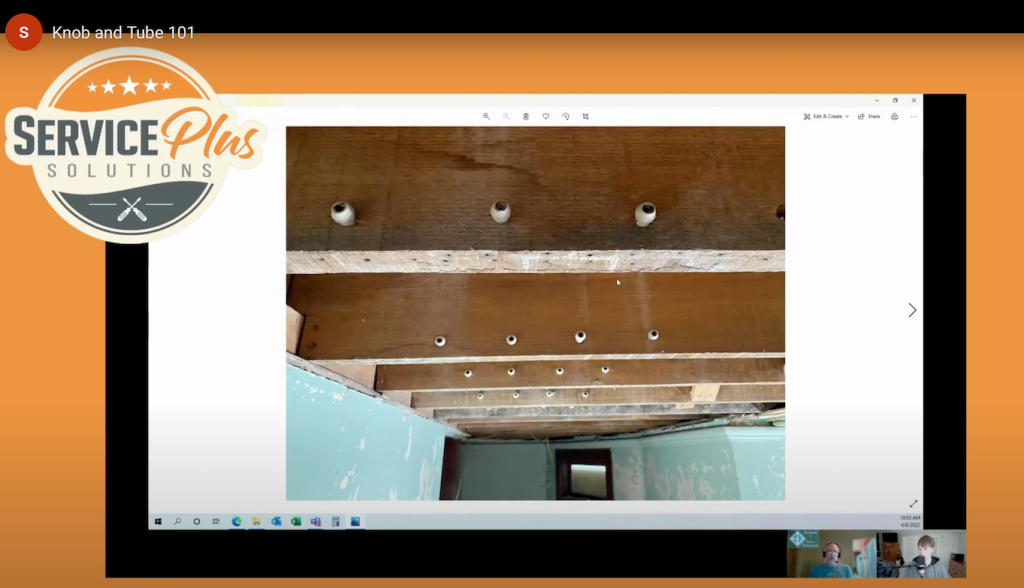

In “Knob and Tube 101,” one of a series of Service Plus Solutions’ videos on electrical issues, David the “Electrician Educator” points out the ordered spacing between the insulators that secured the conductors from and through one joist to the next (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XRUMOkX4C2U).

Electricity was installed in the home of Banker J.P. Morgan in 1882. But for most, the electrification required to illuminate a home remained out of reach. By 1915, a year after the outbreak of the First World War, electricity had been brought to only 8% of American homes. After a wartime power crisis in 1918, the consolidation of electrical supply became a national objective (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Electrification). The residential installation of knob-and-tube wiring systems continued through the 1930s.

Ω

Stay tuned for part 2 and more on knob-and-tube features and foibles including electric fields, wiring runs as antennas, modified knob-and-tube systems, and the dangerous shortcuts all too commonly taken by contractors and others who are not licensed electricians.